While not all of the sites described below are included in the suggested walk, all are marked on the map.

You can also download this map (PDF 1.5MB).

From the drains and sewers under the surface of the ground to spectacular fountains in parks and plazas, the city is full of water features. Some you are meant to ignore, some are there to be noticed and enjoyed.

This water-divining guide reveals Sydney’s well-springs and early feats of water engineering.

Across the length and breadth of central Sydney, you will find high-concept water sculptures, ponds for reflection, pools for play, and places to spend a penny.

Please allow about 2 hours for this walk.

While not all of the sites mentioned in this brochure are included in the suggested walk, all are marked on the map.

Start at the Tank Stream Sculpture, Location 1.

Cover image: The Archaeology of Bathing, Woolloomooloo (Photograph: Mal Booth)

While not all of the sites described below are included in the suggested walk, all are marked on the map.

You can also download this map (PDF 1.5MB).

(Photograph: Richard Glover / City of Sydney)

The settlement of Sydney was centred on a stream of fresh water that emptied into Sydney Cove. This sculpture by Stephen Walker was donated to the city by Sydney Morning Herald publisher John Fairfax & Sons in 1981.

The cascading fountain with bronze animals is an invitation to children to play.

Its dedication “to all the children who have played around the Tank Stream” calls to mind the human landscape of this area before it was a city.

(Photograph: Brett Boardman/City of Sydney)

Circular Quay encroaches over the natural shoreline of Sydney Cove.

At East Circular Quay, the 1788 shoreline is indicated in the granite paving by cast bronze discs.

The first constructed shoreline, reclaimed to form Circular Quay, is mapped by a continuous band of white granite.

Colonial brick barrel drains run beneath the Museum of Sydney. (Photograph: James Horan for Sydney Living Museums)

Tangible reminders of 19th century water engineering include exposed drains at the Museum of Sydney (3), the Conservatorium of Music (4) and the General Post Office (5).

The town’s original water source was the Tank Stream, but pollution soon made its water unsuitable for domestic use. The completion of Busby’s Bore in 1837 enabled the delivery of fresh water to the town centre from Lachlan Swamps (now part of Centennial Park).

Barrel drain dating to 1840s revealed in archaeological excavations at the Conservatorium of Music in 1998. (Image courtesy Casey & Lowe Pty Ltd)

The building which now houses the Sydney Conservatorium of Music was designed by convict architect Francis Greenway and commissioned by Governor Macquarie.

Completed in 1821, its original purpose was stables for nearby Government House.

Archaeological excavations undertaken in 1998 uncovered the remains of a colonial drainage system.

(Image courtesy GPO Grand)

The General Post Office (GPO) was constructed in stages from 1866 to 1891. It is the most notable work in the city by Colonial Architect James Barnet.

In the late 1990s, when the site was redeveloped into a hotel, major conservation works were undertaken. Down in the basement, parts of Sydney’s first water supply, the Tank Stream, were uncovered.

If you enter the building directly under the clock tower and head downstairs, you will find an exhibition of objects found in the archaeological dig, as well as information and artefacts relating to the Tank Stream.

Busby’s Bore delivery system in Hyde Park – undated watercolour painting possibly by C.H. Woolcott. (Image: State Library of NSW, SSV1/WAT/1)

The main public outlet for Busby’s Bore was a pipe raised on trestles which cut across Hyde Park, where Sydneysiders would queue to purchase water at 3 pence per bucket.

It’s not certain where in Hyde Park this water service was situated.

But today, Busby’s Bore is commemorated by a fountain in Hyde Park North.

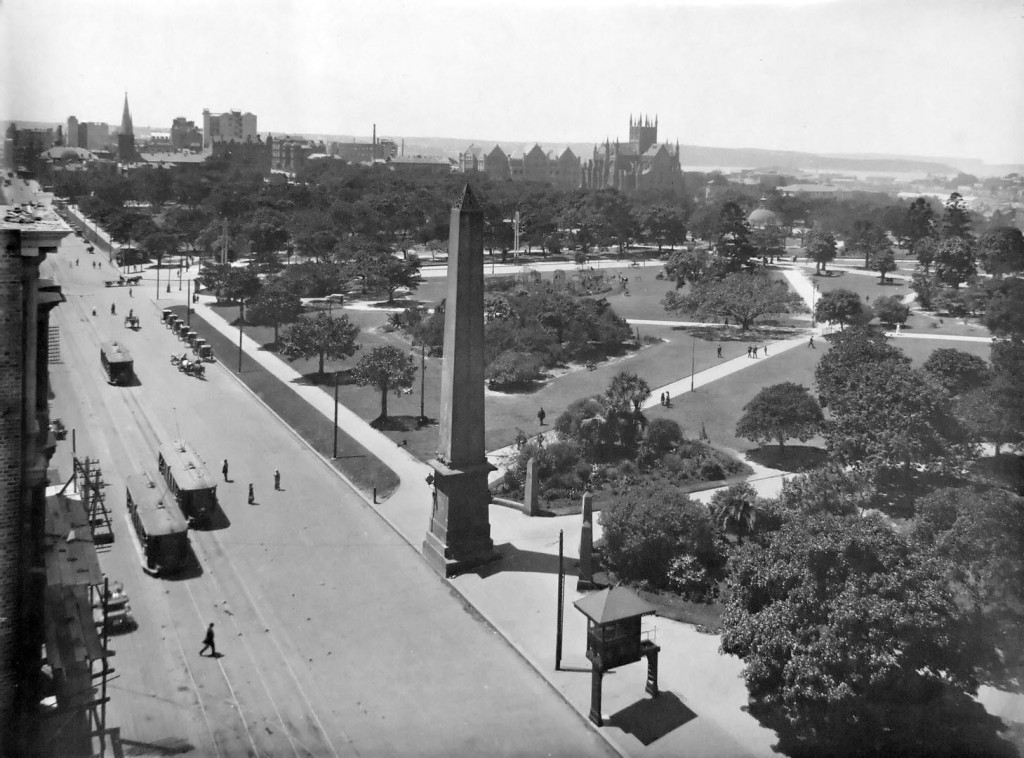

Looking north along Elizabeth Street c.1910 (Photograph: City of Sydney Archives)

The obelisk on Elizabeth Street is one of the earliest monuments recording the good works of a Sydney mayor.

It was built in 1857 and unveiled by Mayor George Thornton.

The monument is actually a sewer vent, which provoked many jokes and led to it being nicknamed “Thornton’s Scent Bottle”.

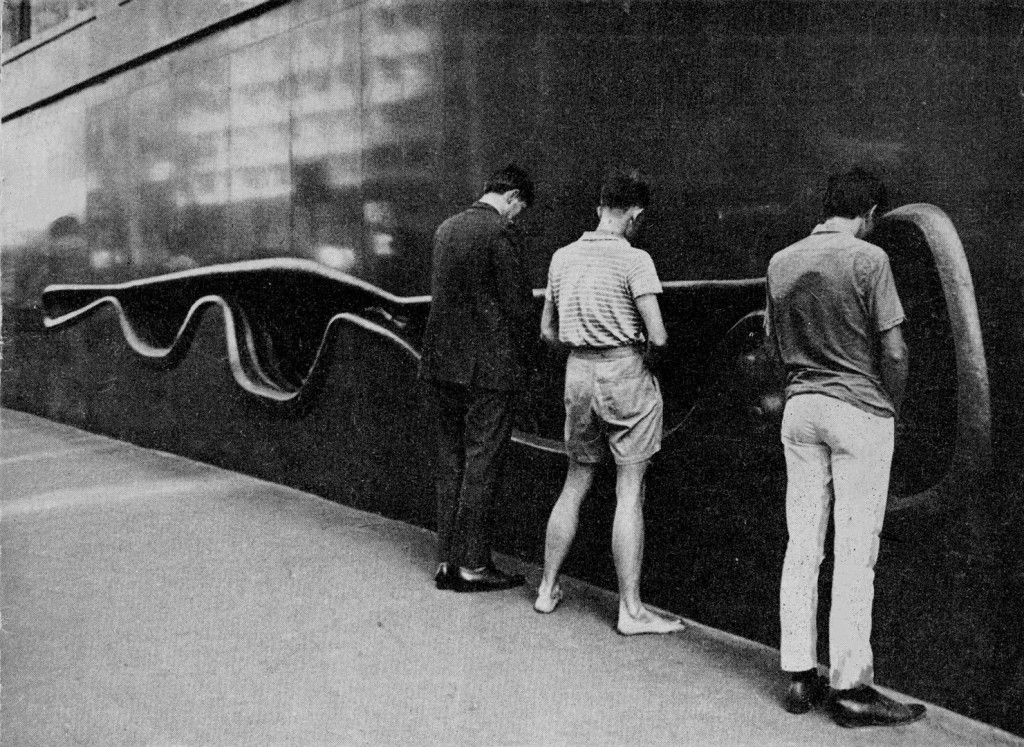

“An attractive bronze urinal” from Oz magazine (Reproduced by permission of Richard Neville)

An early example of public art commissioned by the private sector, The P&O Building Fountain by Tom Bass was installed in 1963.

Oz magazine in February 1964 published a satirical photograph that showed three men apparently peeing in the fountain.

Since then the work has been commonly referred to as “The Urinal”.

The photograph was the subject of a legal battle during which the editors of Oz magazine were accused of promoting “public pissing”.

The artwork continues today to provoke attention because of this history and because of its distinctive structure.

(Photograph: Jamie Williams photography)

“The Little Pig” was a gift to the city of Sydney from the Marchesa Fiaschi Torrigiani as a memorial to Thomas Fiaschi and Piero Fiaschi, her brother and father respectively, who were eminent doctors at Sydney Hospital.

Sydney’s Il Porcellino is an exact replica of the bronze monument known as Porcellino, a 1547 sculpture of a wild boar by Pietro Battiste Tacca which stands in the straw market in the heart of Florence.

It is believed to bring good luck if passers-by rub its nose and drop coins into the base pool, and is placed here to help raise funds for the hospital.

(Photograph: Sally Couacaud/City of Sydney)

Dedicated to the memory of Robert Brough (1857–1906), a popular Sydney actor, this magnificent Victorian fountain is tucked away in the northern courtyard of Sydney Hospital.

The distinctly Australian design comprises a group of brolgas surmounted by black swans displaying their crimson beaks.

The fountain was imported from the Colebrookdale Factory in England and was installed near the Nightingale Wing of the hospital in 1907.

(Photograph: Jamie Williams photography)

Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens cover the area which the original clans of Sydney called Wahganmuggalee, later renamed Farm Cove by Governor Arthur Phillip.

It was once the hunting and ceremonial ground for the Eora people. Here too, the British made their first attempts to grow crops.

Brenda Croft’s art installation Wuganmagulya (Farm Cove) is set into the foreshore walk around the cove.

It pays homage to the Eora and other clans who travelled great distances to attend ceremonies here. The figures depict Sydney rock carvings.

(Photograph: Brett Boardman/City of Sydney)

Among the first harbour baths to be built in Sydney were those opened by Esther Biggs in 1833 on the sheltered shores of Woolloomooloo Bay.

Robyn Bracken’s installation The Archaeology of Bathing (1999) traces the perimeter of the Domain Baths for Ladies.

The stair, cage and portal frame recall the enclosed spaces of early bathing machines, used to shield women from sharks and the attention of men as they bathed.

As the inscription on the timber plaque says, a bathing machine was part of Esther Biggs’ offer to her patrons.

Saluting the naval presence across the bay, the inscribed message appears in Morse code as well as text.

(Photograph: City of Sydney Archives)

An art nouveau bronze statue of a young girl standing amid reeds, a heron and frogs beckons people to drink at the red granite drinking fountain near the Woolloomooloo Gate in Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens.

The fountain, unveiled by the Premier Sir Henry Parkes in 1889, was a gift from the Levy family in memory of Lewis Wolfe Levy (1815–85), politician and businessman.

The statue, by the English sculptor Charles Bell Birch (1832–93), is an important example of art nouveau in Sydney.

Sketch of the long-gone Bent Street fountain by Grace Hendy-Pooley, 1886. (Image: State Library of NSW)

In the 19th century, many houses were built without water connections, so public drinking fountains were essential. Many have disappeared, for example the Bent Street fountain (14), an early Sydney landmark.

The fountain started as a stone octagon receptacle, built around 1810, which collected the fresh water of the natural spring on the site that gave Spring Street its name.

Over time the fountain was improved with a pump, and enclosed within a palisade.

The whole thing was dismantled to make way for the electric trams in 1905.

(Photograph: City of Sydney)

Given the scarcity of domestic plumbing in colonial Sydney, Merchant John Frazer’s gift of two drinking fountains to the people of Sydney in the 1880s was a generous and welcome gesture.

Unlike the Bent Street fountain (14), these two imposing fountains have survived, even if they no longer offer water to quench the thirst of passers-by.

Both were designed by the City Architect, Thomas Sapsford, and carved in Pyrmont sandstone by Lawrence Beveridge.

The Frazer Fountain (15) at the intersection of Art Gallery Road and Prince Albert Road was installed in 1884.

Designed in the Italian Renaissance style, it is more ornate than its Gothic style twin in Hyde Park (16).

Frazer Fountain, 1932. (Image: City of Sydney Archives)

The original design of the Frazer Memorial Fountains featured cups dangling from the large water basin for people to take a drink. Every detail in the design was considered, with the taps made of bronze in the shape of dolphins.

Eventually the City council realised the health hazards of communal cups. In 1934 they replaced the basin and taps with the new ‘bubble stream’ design.

First installed at the Hyde Park entrance opposite Oxford Street, this fountain was moved near the Pool of Reflection in 1917 to make way for the Emden Gun.

In 1934 it was moved once again to its current location near College Street when Hyde Park South was remodelled.

(Photograph: Brett Boardman/Spackman Mossop Michaels)

This environmental artwork by Anita Glesta was inspired by the Yurong Creek which once ran from the edge of Cook + Phillip Park through the mangrove swamps down into Woolloomooloo Bay.

Roughly hewn boulders of sandstone, reflecting the natural and cultural heritage of the area, and original pavers from the former park have been arranged to form a course for the creek which flows down three terraces of gardens, retracing the path of the original.

(Photograph: City of Sydney)

The many uses of water at Cook + Phillip Park are testament to Sydney’s love of water — from the harbour to Yurong Creek, from bathing to competition, and from playing to meditation.

The swimming pools in the complex are used for children’s games and sporting events.

The Yurong Water Gardens and the pools of reflection on College Street act as major structural elements to balance the weight of the roof of the pools below.

Inside the aquatic centre, adorning the walls of the main pool, eight large panels painted by Sydney artist Wendy Sharpe depict the life story of Australian champion swimmer, aquatic performer and actress, Annette Kellermann (1886-1975).

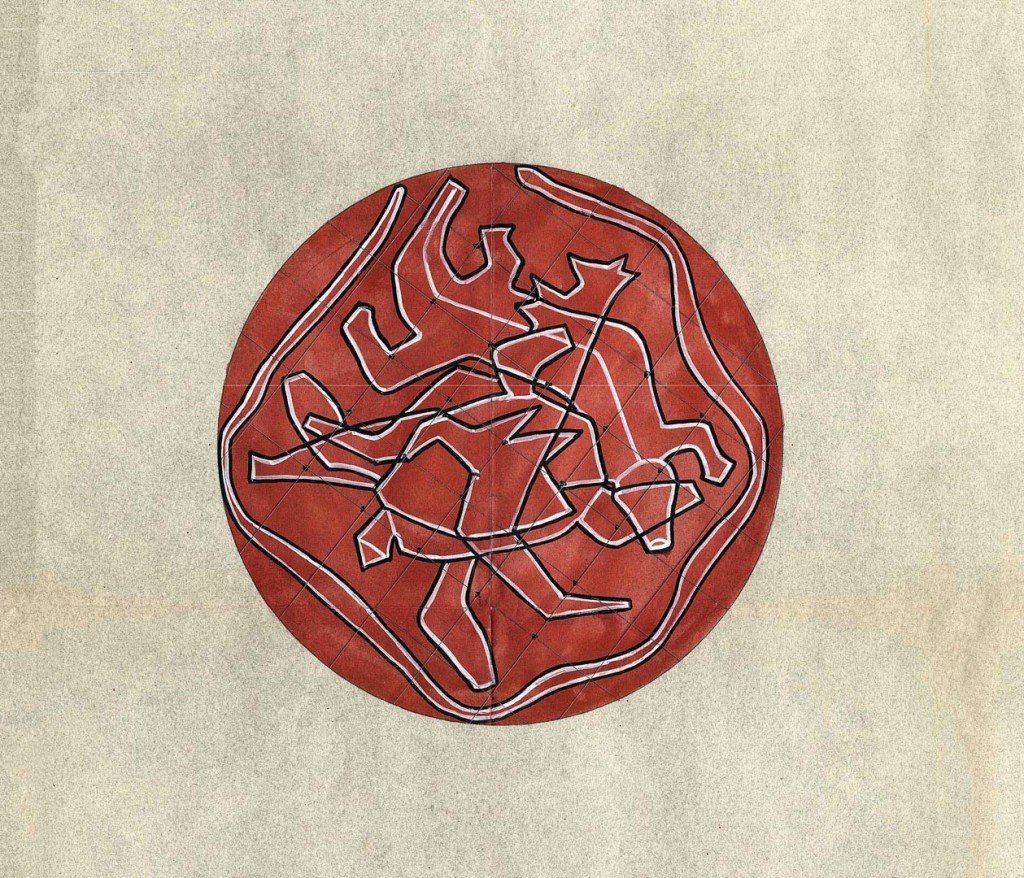

Original mosaic design by Lyndon Dadswell. (Image: City of Sydney Archives)

This fountain is part of an elaborate memorial to King George V and King George VI. Previously, a bandstand stood on the site. Officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II in February 1954, Sandringham Garden and Memorial Gates are testament to the royal fever that gripped Australia in the early 1950s.

But the mosaic on the base of the fountain tells a different story.

Its designer Lyndon Dadswell wanted to give the memorial to the two dead kings an Australian flavour by incorporating motifs inspired by Aboriginal art.

It was an emerging trend at this time for Australian artists and designers to take inspiration from Aboriginal art, without considering the question of cultural appropriation.

This mosaic is believed to be the first example of the use of Aboriginal-inspired motifs in an urban architectural context in Australia.

Anzac Memorial and Pool of Reflection c.1960s (Photograph: City of Sydney Archives)

The Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park South was built to commemorate the men and women who served in World War I.

But during the period of its construction in the early 1930s, the land fit for heroes was no longer providing the rewards and jobs hoped for, and the country was in a profound economic depression.

The Pool of Remembrance had been part of architect Bruce Dellit’s original design for the memorial, but without the State Unemployment Relief Fund subsidising the project, the pool might not have been completed in time for the memorial’s official opening in the November 1934.

(Photograph: City of Sydney Archives)

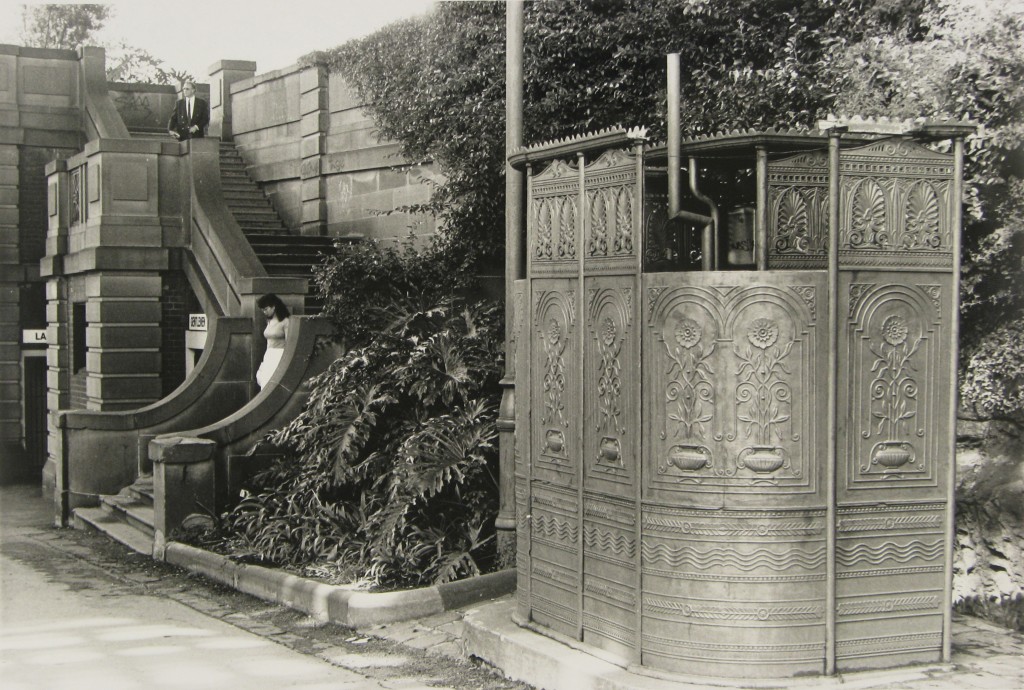

Sydney’s first public toilets were two cast-iron urinals purchased by the council in 1880.

One such early “pissoir” can be found under the approaches to the Harbour Bridge (21).

This cast-iron urinal by the stairs from lower George Street originally stood on Observatory Hill.

Ladies’ public convenience in Hyde Park, 1932. (Photograph: City of Sydney Archives)

It is unclear just what the ladies did before 1910 when their first public convenience was built in Hyde Park. The Lord Mayor in 1916 declared that facilities for ladies should be provided “under cover of chalet or cloak room accommodation so as not to be made too conspicuous.”

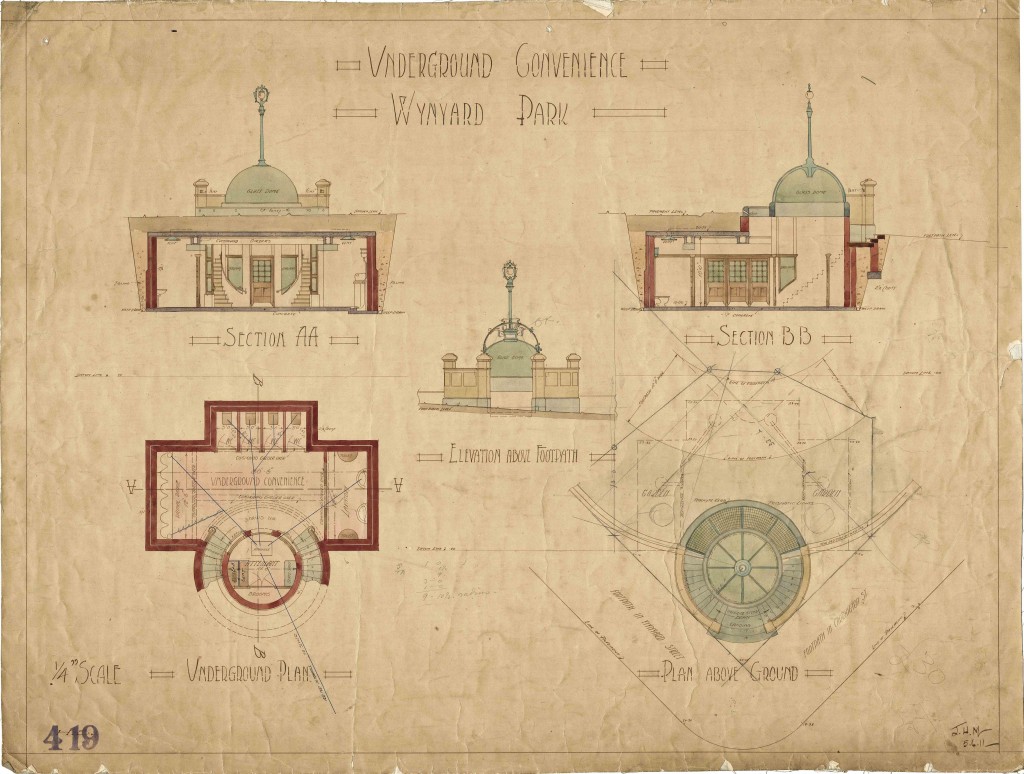

A range of substantial men’s loos were built in the early 20th century, many underground.

Filled-in or repurposed reminders of these can be found at Hyde Park (22), Wynyard Park (23) and Macquarie Place (24).

(Image: City of Sydney Archives)

Plans for the Wynyard underground convenience, 1911.

(Photograph: City of Sydney Archives)

Men’s convenience in Macquarie Place, c.1934.

(Photograph: Jamie Williams Photography)

This distinctive art deco showpiece is the legacy of a private citizen, J F Archibald, and is quintessentially Sydney.

The fountain was built in Hyde Park North in 1932 to commemorate the association between Australia and France in World War I.

The work of French sculptor Francois Sicard, it depicts a bronze Apollo surrounded by other mythical figures.